Article published in its entirely, without consent, courtesy of the Globe & Mail

It’s safe, it’s effective, and it’s been approved by Health Canada for treating depression since 2002. Yet, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) – a non-invasive brain stimulation treatment that brings relief to patients who do not respond to antidepressants – remains out of reach for most Canadians because most provinces don’t fund it, and the cost at private clinics can be out of reach.

In an effort to make it more efficient, cost-effective and accessible, a team of Canadian researchers investigated a new method of administering rTMS that makes treatment more than 10 times faster. In a large, landmark study published in the journal The Lancet last year, they showed that by using a different pattern of currents, rTMS could be just as effectively delivered in, shorter, considerably cheaper three-minute sessions, instead of the standard 37 minutes.

Now Dr. Jonathan Downar, who is a scientist at the Krembil Research Institute at Toronto’s University Health Network, wants to take this work another step further. He believes that if rTMS can be safely, cheaply and effectively self-administered by patients at home, many more will be able to receive the treatment.

During a typical session at a clinic, the patient sits back in a chair, while a doctor or technician positions a magnetic coil against his or her forehead. The coil generates a magnetic field strong enough to induce currents in targeted areas of the brain to regulate brain circuits that are not working properly. Roughly 30 per cent of patients with depression do not respond to antidepressants. But with rTMS, about 50 per cent see a significant reduction in their symptoms, including 30 per cent who achieve remission.

Patients typically need 20 to 30 sessions, as well as periodic follow-up “booster” sessions, since their symptoms tend to return after several months.

Dr. Downar is looking to study whether a portable rTMS device that is on the market and already approved by Health Canada can produce the same effect on patients at home as the ones used in clinics. (He declined to name the device to avoid promoting the manufacturer.) He suggests that if his clinic were to issue the devices to patients and show them how to administer rTMS on themselves, it would save them from having technicians or doctors deliver the treatment. Plus, since patients can often go months between courses of treatment, the clinic could lend out the devices temporarily, so that multiple patients could use the same one. If it works, he believes the cost of rTMS treatment could be further reduced to less than $5 per session.

“Health Canada-approved home brain stimulation that you can get from your doctor is coming,” says Dr. Downar, co-director of the University Health Network rTMS clinic, though he cautions, “it is at least five years away.”

Health professionals currently advise against people using any type of brain stimulation on their own without expert guidance.

For Julie Marriott, 69, the prospect of avoiding the long daily drive from her home in Ancaster, Ont., to Toronto for treatment and some day being able to administer it in the comfort of her own home, would be a “life-changer”.

In the meantime, Dr. Downar and his colleagues say rTMS could be made widely available to Canadians who need it now, if only it were publicly funded.

RTMS is only publicly covered in Quebec, Saskatchewan, Yukon and at certain Alberta Health Services centres. According to Alberta’s Ministry of Health, publicly funded treatment will be available in Edmonton as of this January, and it will be available in Calgary later this year. But Canadians suffering from treatment-resistant depression are out of luck if they live outside major cities, or are unable to afford the treatment at the few private clinics that offer it. (Using the three-minute version, a full course of treatment costs approximately $1,500, compared with $3,000 for a standard course.)

“We need to level the playing field here a bit, and provide access [to rTMS] across the country,” says Dr. Fidel Vila-Rodriguez, director of the non-invasive neurostimulation therapies laboratory at the University of British Columbia.

In B.C., he says his clinic, which relies on research grants, is the only site in the province to offer rTMS at no cost to patients. Although rTMS was offered in Victoria from October, 2016, to March, 2017, that program was halted because the treatment is not a publicly funded health care service in B.C., a spokesperson for B.C.’s Island Health, formerly known as the Vancouver Island Health Authority, said in an e-mail.

Encouraged by the results of The Lancet study, however, Dr. Vila-Rodriguez, who was a co-author, says he made a submission to the B.C. Health Technology Assessment committee in December, suggesting that it review rTMS for treating depression. The committee is responsible for making recommendations about health services and medical devices to the Ministry of Health.

Ontario’s health technology assessment committee recommended publicly funding rTMS in 2016. However, the province has yet to cover the treatment. In an e-mail, a spokesperson for the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care said the ministry “is continuing to review the provision of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the province.”

In Toronto, Dr. Daniel Blumberger, the lead author of The Lancet study, says it is important for governments to consider funding rTMS, since it can prevent patients from requiring other treatments, like electroconvulsive therapy, which involves putting a patient under general anaesthetic and inducing a seizure. Electroconvulsive therapy also has the potential for more side effects.

“At the end of the day, the investment [in rTMS] could lead to very good returns in the long term by getting more people back to work, getting more people better, and reducing the societal cost of treatment-resistant depression,” says Dr. Blumberger, medical head and co-director of the Temerty Centre for Therapeutic Brain Intervention at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. “Once people get into that cycle of not getting better, it’s harder to get them out and the costs increase exponentially.”

Dr. Downar points out that rTMS is covered across the U.S. by Medicare, the national publicly-funded insurance program. And based on the Canadian findings in The Lancet, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved of the three-minute “theta burst” form of rTMS in August, allowing U.S. doctors to see many more patients.

“It would be nice if Canadian taxpayer funded research actually led to better access for Canadians,” he says.

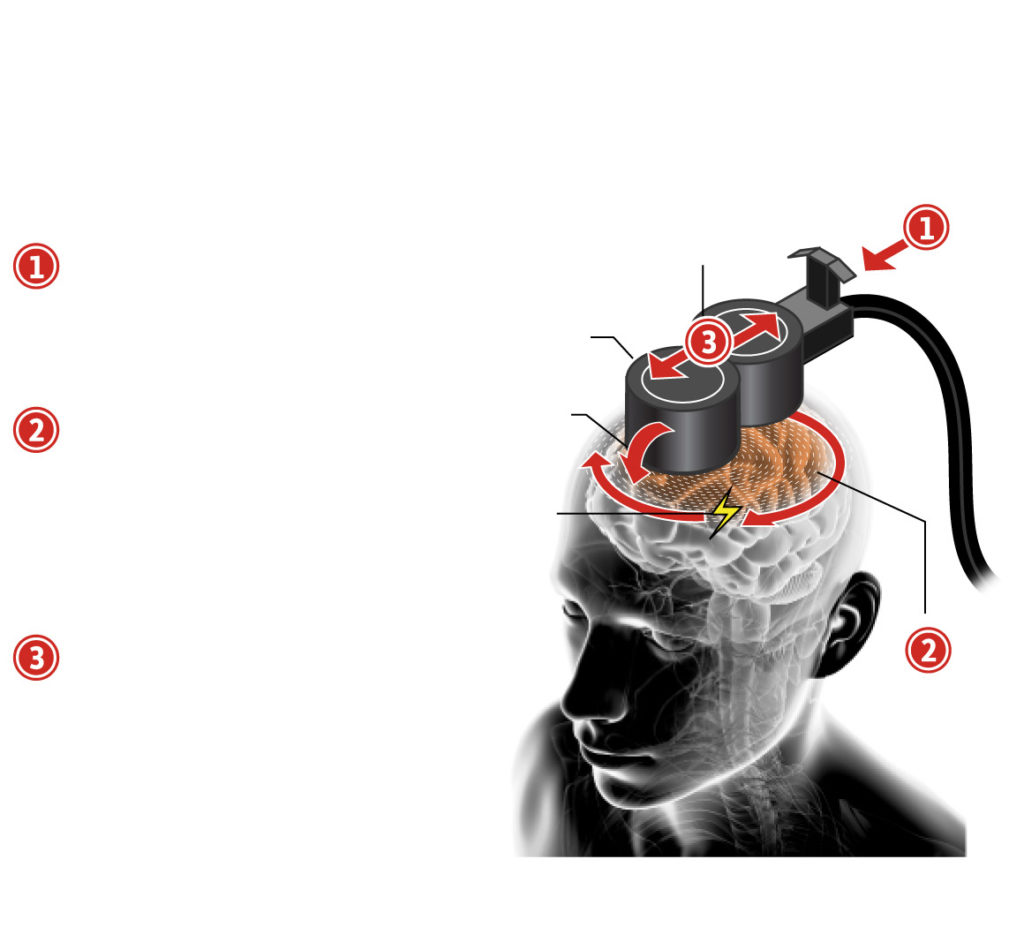

How does rTMS work?

Using a new method of Repetitive Transcranial Stimulation (rTMS), called theta burst stimulation, Canadian researchers have shown the same positive results as previous versions can be achieved in three-minute sessions instead of the more typical 37 minutes. The idea is to change the brain patterns involved in depression (and other conditions for which rTMS is being tested).

- Pulses

The patient sits back in a chair while a doctor or technician positions a magnetic coil against his or her forehead.

2. Magnetic coils Positioning

The coil generates a magnetic field strong enough to induce currents in targeted areas of the brain to regulate brain circuits that are not working properly.

3. Electric currents Theta burst stimulation

involves a different pattern of pulses by firing three pulses at 50 Hz repeated five times per second.

Electromagnetic field Process has been simplified for diagram

Leave a Reply